Frankly? It doesn’t really matter.

Photographers and cinematographers like cameras. I like cameras. I like fidgeting with the knobs and buttons, and rings and levers. I like feeling their heft in my hands. So, I buy cameras. Lots of them.

But that’s not necessarily a good idea. Because it’s expensive. And because cameras don’t really matter.

What matters is seeing. You don’t need a camera for that. Just a pair of good eyes and curiosity. And knowing how to translate what you see into a photo.

And truly understand what you can expect from your camera, and what not.

Use your iPhone. You can make wonderful photos with an iPhone, if you understand under what circumstances it will give you good results, and when not. If you understand that you cannot control depth of field on an iPhone (at least not readily), that it doesn’t always work well in poor light, that you won’t be able to have 50cm x 60cm blowouts printed.

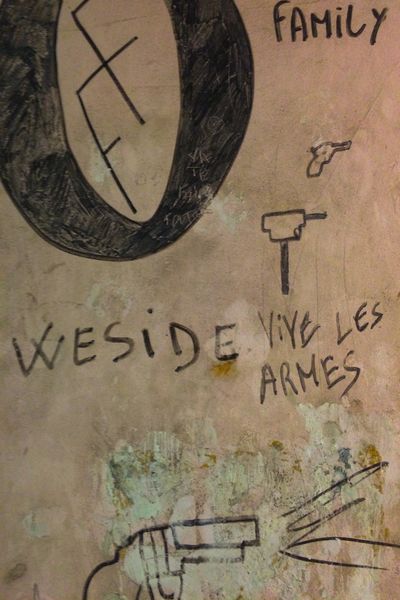

A few years ago, I had an exhibition of photos taken with an iPhone 5 in an old French prison. They were all sold. You could tell (well, I could) they were taken with an iPhone, but the buyers didn’t care: they liked what they saw. They saw what I had seen, and felt what I had felt: emotion, outrage, or curiosity. Which is what it’s all about: sharing emotions through photos.

Incidentally, look at the bottom right photo: overall the iPhone did a good job. I had to tweak the photo only lightly: increase shadows a bit, add some saturation, straighten and crop the photo, and that’s it. But as you can tell, the iPhone couldn’t handle the highlights (the overhead lights in the hallway): they’re totally blown out. This is beyond redemption. A regular camera probably would have kept more information in the highlights. Another thing: when you zoom in, all sorts of artifacts start showing. The iPhone software accomplishes near miracles to produce a good looking photo, but it shows when you enlarge it too much. I hear that more recent smartphones do a much better job.

These days, the sky is the limit. Nikon, Canon, Fuji, etc., all make cameras that take multi-million-pixel photos, have 90 or more autofocus points, can track moving objects, sport extremely refined automated exposure, and a user manual 300 pages thick. You can literally do anything with them, regardless of circumstances, lighting, distance, whatever. Basically, all you have to do is point the camera in the overall direction of your subject, and push the release button. You’ll come out with a technically perfect photo. Provided of course, that you slugged your way through the manual. And Japanese manuals tend to be formidably abstruse and hermetic.

Of course, in the hands of a knowledgeable photographer, these cameras are redoubtable instruments. They changed the life of sports photographers, wildlife photographers, and reporters, and infinitely increased the conditions in which really outstanding photos can be made.

But what none of these cameras can do, is see. They never will. They have sight, but cannot see. Only you can.

Which is my point, really.

Until a few years ago, I used an old Leica M3 from the ‘sixties and shot on film. It was a 100% manual camera: no exposure metering, no a utofocus, no nothing. Everything had to be set manually. It really concentrated the mind: focus, aperture, exposure time required reflection and careful consideration. I liked that, the thought, the concentration, the decision-making. Should I use a smaller aperture, to increase depth of field? But then I would have to increase exposure time (remember, with film you can’t just increase ISO ([1])), and risk movement blur. It was a slow, deliberate process. Not like the spray and pray approach that’s become the norm with today’s fully automated DSLRs.

utofocus, no nothing. Everything had to be set manually. It really concentrated the mind: focus, aperture, exposure time required reflection and careful consideration. I liked that, the thought, the concentration, the decision-making. Should I use a smaller aperture, to increase depth of field? But then I would have to increase exposure time (remember, with film you can’t just increase ISO ([1])), and risk movement blur. It was a slow, deliberate process. Not like the spray and pray approach that’s become the norm with today’s fully automated DSLRs.

But the utter simplicity of the camera (the manual was 10 or 12 pages) allowed me to concentrate on the task at hand: photographing something I had seen. I didn’t have to wade through umpteen menu screens to find the setting I needed to change: all I had to do was set the focusing ring, the aperture ring and the exposure ring.

When the cost of shooting on film became prohibitive ([2]), I moved to digital cameras. I looked for something that worked like aLeica, or close to it (digital Leica M cameras were way too expensive).I tried Sony, cheaper Leicas, Canon, Fuji… The closestto a Leica M was theFujifilm X100. It’s a gorgeous looking thing. You can make it work like a fully manual camera. The image quality is stunning. But the manual is hopeless, the menu system a nightmare. I sold it. It was interfering with my photo-making.

When the cost of shooting on film became prohibitive ([2]), I moved to digital cameras. I looked for something that worked like aLeica, or close to it (digital Leica M cameras were way too expensive).I tried Sony, cheaper Leicas, Canon, Fuji… The closestto a Leica M was theFujifilm X100. It’s a gorgeous looking thing. You can make it work like a fully manual camera. The image quality is stunning. But the manual is hopeless, the menu system a nightmare. I sold it. It was interfering with my photo-making.

I’d recommend it to anyone who is looking for a high-quality camera, and who isn’t fazed by the (to me) ludicrously complicated operation.

I finally settled on the diminutive RICOH GR III. The images are fantastic, operation of the camera is reasonably simple and straightforward, and it’s small and lightweight. Now that second-hand digital Leica Ms become affordable, I may return to my old love.

Remember one thing, though: the camera is not important. Like George Perkins Marsh so elegantly stated in 1863: “the power most important to cultivate... is that of seeing... Sight is a faculty; seeing, an art”.

_________________________________________

[1] In fact you can, but there is a price to pay. You can increase ISO (to some extent), but you’ll have to adapt development time and/or developer strength. And the quality of the negative may be affected.

[2] Actually, the film and development were (and are) cheap. But since I no longer had access to a dark room, I had the negatives scanned, and processed the scans on the PC. And high quality scans are very expensive.